The Science of Jaguars: The Largest Cats of Belize

WHAT IS A JAGUAR?

The jaguar (Panthera onca) is the largest wild cat in the Western Hemisphere, and the third-largest wild cat in the world. Jaguars are the only “true” big cats- that is, members of the genus Panthera, which includes lions, tigers, and leopards- found in the Americas.

Junior Buddy, a jaguar ambassador at the Belize Zoo from February 2007 to December 2019. Photo by Inspire EdVentures.

Jaguars are compact, muscular cats, with relatively short limbs, square heads, powerful jaws, and small, round ears. Though the size of these cats varies greatly throughout their range, jaguars are typically 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 meters) in length, stand 2 to 2.5 feet (0.68 to 0.75 meters) at the shoulder, and weigh between 100 and 220 pounds (45 to 100 kilograms). Like many mammals, males are larger than females; a male jaguar may be up to 20% larger than a female. The largest jaguars can reach well over 6.5 feet (2 meters) and weigh nearly 300 pounds (150 kilograms)!

A jaguar’s coat ranges from yellow to tan or brown in coloration, with lighter coloration on the throat, belly, and insides of the legs. Their coats are patterned with black spots, or rosettes, along the neck, back, sides, and limbs. (A rosette is a circular-shaped spot, often with smaller dots inside.) These patterns are completely unique to each jaguar; in fact, jaguars in the wild can be identified and even tracked through analysis of their spot patterns.

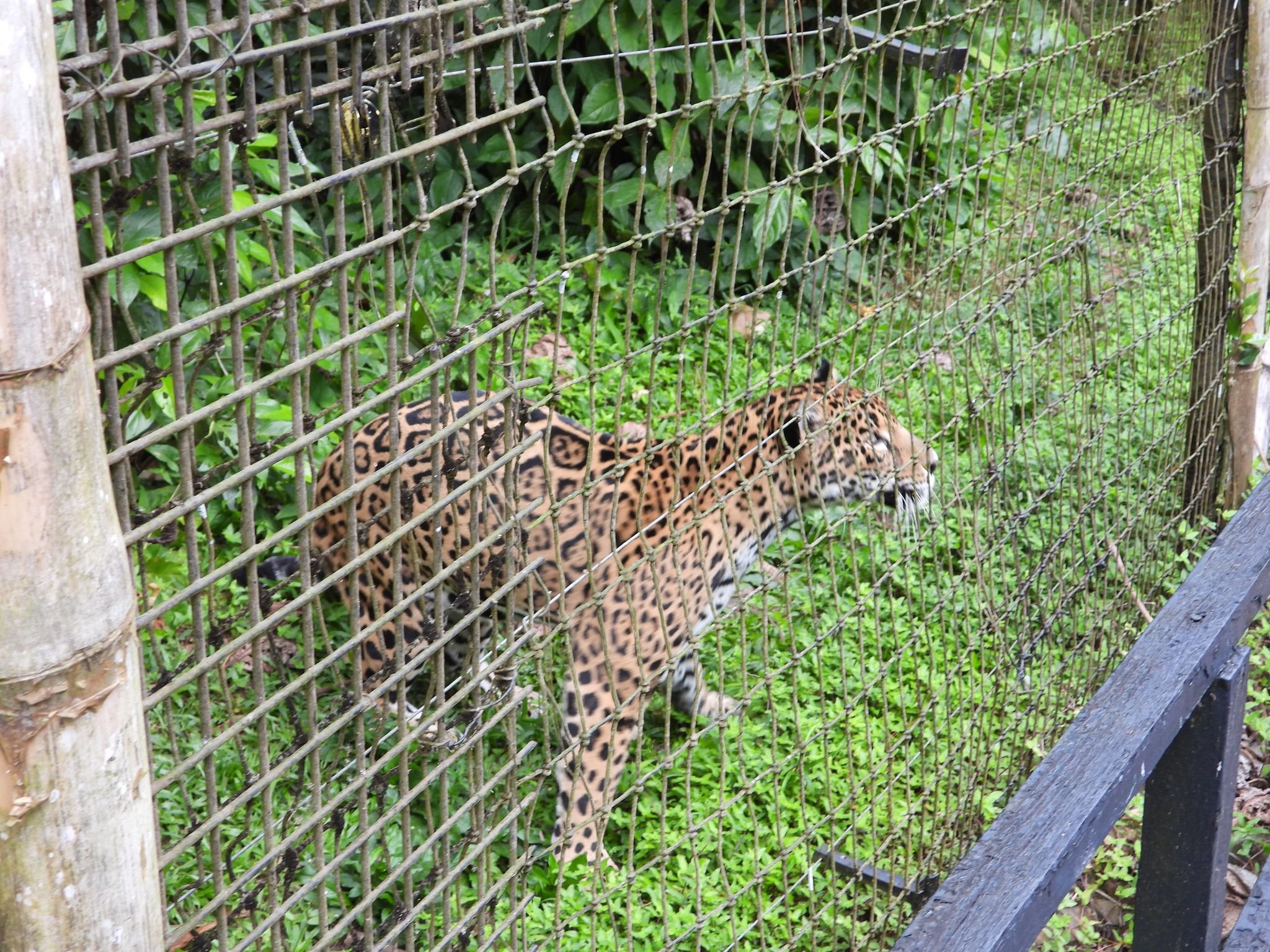

A jaguar at the Belize Zoo showing off its unique spot pattern. Photo by Inspire EdVentures.

In rare cases, a jaguar may be born with a seemingly solid black coat. This condition, known as melanism, is a genetic syndrome causing overproduction of the pigment melanin. Melanistic jaguars are sometimes called black panthers, a name they share with melanistic leopards found in Africa and Asia. Though melanistic jaguars and leopards may look similar, melanism in jaguars is carried on a dominant allele, whereas melanism in leopards is carried on a recessive allele. (That is, a leopard needs two copies of the associated gene to have a black coat, whereas jaguars need only one copy.) Melanism is believed to be more common in jaguars living in deep rainforest, such as those found in Central America and the Amazon basin.

Due to differences in appearance and habitat, jaguars have historically been divided into multiple subspecies, including Panthera onca centralis (the Central American jaguar) and Panthera onca onca (the Brazilian or Amazonian jaguar). However, studies of jaguar genetics and morphology (physical structure) have found significant similarities between jaguars of different subspecies, casting these divisions into doubt. In 2017, a taxonomic revision classified Panthera onca as a monotypic species, meaning a species without official subspecies. All jaguars are now defined as Panthera onca.

WHERE ARE JAGUARS FOUND?

How did jaguars become the only big cats of the Americas? The history of jaguars in the Western Hemisphere begins with the Bering Land Bridge, or Beringia, which connected northeastern Asia to modern-day Alaska during the late Pleistocene Epoch (until around 11,700 years ago). Ancestors of today’s jaguars likely crossed this bridge into North America, then spread throughout the continent and eventually into South America.

Fossil evidence shows ancient jaguars were widespread throughout the Americas, including in the United States as far north as Wisconsin. These Pleistocene jaguars- Panthera onca augusta in North America and Panthera onca mesembrina in South America- were significantly larger than the modern Panthera onca.

The fossilized lower jaw of Panthera onca augusta, on display at the Tellus Science Museum in Cartersville, Georgia. Photo credit to Jonathan Chen.

Over time, the jaguars’ range shifted and shrank, becoming concentrated closer to the equator. The original range of Panthera onca stretched from the southern United States to northern Argentina, encompassing a variety of habitats including rainforests, savannas, grasslands, swamps, marshlands, and even deserts.

However, jaguars have been driven out of many of their former areas, largely through hunting and habitat destruction. They are now believed to be extinct in the United States, El Salvador, and Uruguay. The IUCN estimates that jaguars currently inhabit only 51% of their former range, with the most significant population reductions occurring in more arid environments such as the southern United States and northern Mexico.

Map showing estimated current and former range of Panthera onca. Created by user The Emirr as part of the Cypron Map Series using data from the IUCN Red List.

Currently, an estimated 64,000 jaguars exist in the world. According to the IUCN, as much as 89% of these jaguars- up to 54,000 individuals- are found in the Amazon rainforest, mostly in Brazil. Strong populations also exist in the tropics of Central America, including the Cockscomb Basin of Belize.

Interestingly, jaguars tend to be smaller nearer to the equator and larger in the northernmost and southernmost areas of their range; jaguars of Honduras may weigh just over half (125 pounds, or 57 kg) of those found in Brazil (220 pounds, or 100 kg). This variation in size is thought to be correlated with the size of available prey. Jaguars in deep rainforests close to the equator, where prey species are typically small mammals, birds, and reptiles, are smaller than those in more open grasslands or savannas.

WHAT DO JAGUARS EAT?

With over 85 known prey species, jaguars are top predators of any environment they call home. Jaguars mainly eat small mammals, such as agoutis, opossums, armadillos, pacas, and peccaries, but are known to hunt larger animals including deer, capybaras, and even tapirs. (An adult Central American tapir may outweigh an adult jaguar by 200 to 300 pounds, or 90 to 135 kg!) Jaguars also eat reptiles like iguanas, turtles, boas, and caimans, and are often observed fishing for catfish, frogs, and crabs. Even other wild cats aren’t safe from these predators; jaguars have been known to kill and eat unlucky ocelots that cross their paths.

Two prey species of the jaguar: the Central American agouti, Dasyprocta punctata [left], and lowland paca or gibnut, Cuniculus paca [right]. Photos taken by Inspire EdVentures trail camera.

Jaguars are primarily nocturnal, meaning they are most active at night. They are ambush hunters who stalk their prey from thick vegetation or even from the branches of trees before leaping onto the animal’s back and crushing its skull or neck with their powerful jaws. Jaguars have the strongest bite force of any big cat, at 1,500 pounds per square inch (PSI). A human’s bite force is only 70 PSI- not even 5% as strong as a jaguar!

After killing its prey, a jaguar will drag the remains to a secluded area, sometimes for distances of over a mile (1.6 km). The jaguar may return to the kill several times over a period of hours or days, and will eat nearly the entire animal, including bones.

Unfortunately, jaguars will sometimes stray from their usual prey to target livestock, such as cattle, pigs, or horses. These jaguars, called “problem jaguars,” often turn to livestock due to injury or illness that prevents them from pursuing their usual prey. “Problem jaguars” are sometimes trapped and relocated, but are more often killed by farmers and ranchers to protect their livelihoods. As the jaguar’s range and the availability of prey decreases, so increases the probability of this deadly conflict with humans.

Sylvia, one of the Belize Zoo’s ambassador jaguars, was a “problem jaguar” rescued by the Belize Zoo when an injury caused her to begin hunting livestock. Photo by Inspire EdVentures.

Despite their status as top predators, however, incidents of jaguars attacking humans are extremely rare. Jaguars prefer to avoid humans whenever possible; nearly all conflict is driven by humans, either through intentionally hunting jaguars or encroaching into the jaguar’s territory, and is usually fatal for the jaguar.

HOW DO JAGUARS BEHAVE?

Like many (though not all) wild cats, jaguars are solitary animals, meaning that they spend most of their lives on their own. Both male and female jaguars establish their own territories, and a male’s territory may overlap with those of multiple females, though they rarely interact outside of mating. In some areas, a male jaguar’s territory may reach over 38 square miles (100 square kilometers), with a female jaguar’s territory measuring about half that of a male.

Jaguar ranges sometimes overlap with those of pumas (Puma concolor), the second-largest cat in the Americas. Despite jaguars and pumas pursuing similar prey, however, the two species seem to largely avoid each other even in close quarters. In cases when their territories overlap, jaguars are often found closer to water, whereas pumas prefer drier areas.

A puma [top] and jaguar [bottom], taken by the same camera eight days apart. These top predators are known to occasionally inhabit the same areas. Photos taken by Inspire EdVentures trail camera.

Jaguars communicate through vocalizations, scent markings, and perhaps tree scrapings (leaving claw marks on the trunks of trees), though the latter behavior may simply be similar to a domestic cat using a scratching post. (Also similar to domestic cats, jaguars are reactive to catnip, and jaguars in captivity enjoy playing with cardboard boxes!) Vocalizations, such as loud roars, are used to attract other jaguars for mating.

Though jaguars have no strict breeding season- jaguars in captivity will breed at any time of year- in the wild, mating is most common during the rainy season, perhaps because their prey is more plentiful. The timing of the rainy season varies throughout their range, but is mostly associated around the months of November through March or June.

Jaguars are altricial, meaning that their young are completely dependent on their parents at birth, and are cared for solely by the mother. After mating, gestation (pregnancy) lasts an average of 101 days, or just under three and a half months. Between one and four cubs are born per litter, with two cubs as the average. Cubs weigh about 28 ounces (800 grams) at birth, and may gain over 1.5 ounces (43 grams) per day for the first two months of their lives.

Cubs are born toothless and with their eyes closed; a cub’s eyes will open between four days and two weeks after birth, and cubs begin walking at about eighteen days. They will continue nursing for up to six months, and will remain with their mother for up to two years. During these two years, the mother will not mate again, and will in fact avoid adult males, who may kill and even eat her cubs.

Male jaguars reach maturity between 2 to 3 years of age, and females between 1.5 to 2 years. In the wild, jaguars rarely live over 12 or 13 years, but may survive for well over 20 years in captivity!

ARE JAGUARS ENDANGERED?

Jaguars are currently classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN, with a decreasing population throughout their range. Their population has declined an estimated 20-25% over the last 21 years; between 2002 and 2015, their range also declined up to 20%, or over 1.7 million square kilometers (65,600 square miles).

The strongest jaguar populations are found in the Amazon Basin of Brazil and the Selva Maya rainforest of Belize, Guatemala, and southern Mexico. Other populations, including those of northern Argentina and the Cerrado savanna of Brazil, are in greater peril. According to the IUCN, populations over an estimated 12% of the jaguar’s range have a low probability of long-term survival, and will likely face local extinction over the next few generations.

A jaguar in the rainforest of Belize. Photo taken by Inspire EdVentures trail camera.

What is being done to protect jaguars? Wildlife sanctuaries- including the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary of Belize, established in 1986 as the first area specifically for conservation of jaguars- provide much-needed stable habitats for these cats. Conservation organizations of Belize have also fought to protect the Mayan Jaguar Corridor, a six-mile-wide strip of land connecting two larger rainforests. Preservation of the corridor is essential to prevent fragmentation and decline of the Central American jaguar population.

On a local level is the Belize Zoo’s Human-Jaguar Conflict Program, which seeks to prevent jaguars from being killed by local farmers. The Belize Zoo encourages locals to report “problem jaguars”, and will trap and recover these jaguars. In fact, many of the Belize Zoo’s current jaguar ambassadors originated as “problem jaguars” who turned to hunting livestock due to injuries in the wild. These jaguars now reside at the Belize Zoo or other zoos worldwide, helping spread awareness of the stories, struggles, and conservation of Belize’s most beautiful cats.

A jaguar with Belize Zoo Conservation Program Manager Jamal Andrewin-Bohn. The Belize Zoo is a leader in conservation for Central America’s jaguars. Photo by Inspire EdVentures.

Interested in learning more about jaguars? Visit the jaguars of the Belize Zoo with Inspire EdVentures in our Belize Zoo Live! Virtual Tour!

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Wild Cats 101: Black Cats and More on Melanism at Panthera.org

Kevin L. Seymour, Panthera onca, Mammalian Species, Issue 340, 26 October 1989, Pages 1–9, https://doi.org/10.2307/3504096

Nogueira, J. 2009. "Panthera onca" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Panthera_onca/

Quigley, H., Foster, R., Petracca, L., Payan, E., Salom, R. & Harmsen, B. 2017. Panthera onca (errata version published in 2018). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T15953A123791436. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15953A50658693.en.